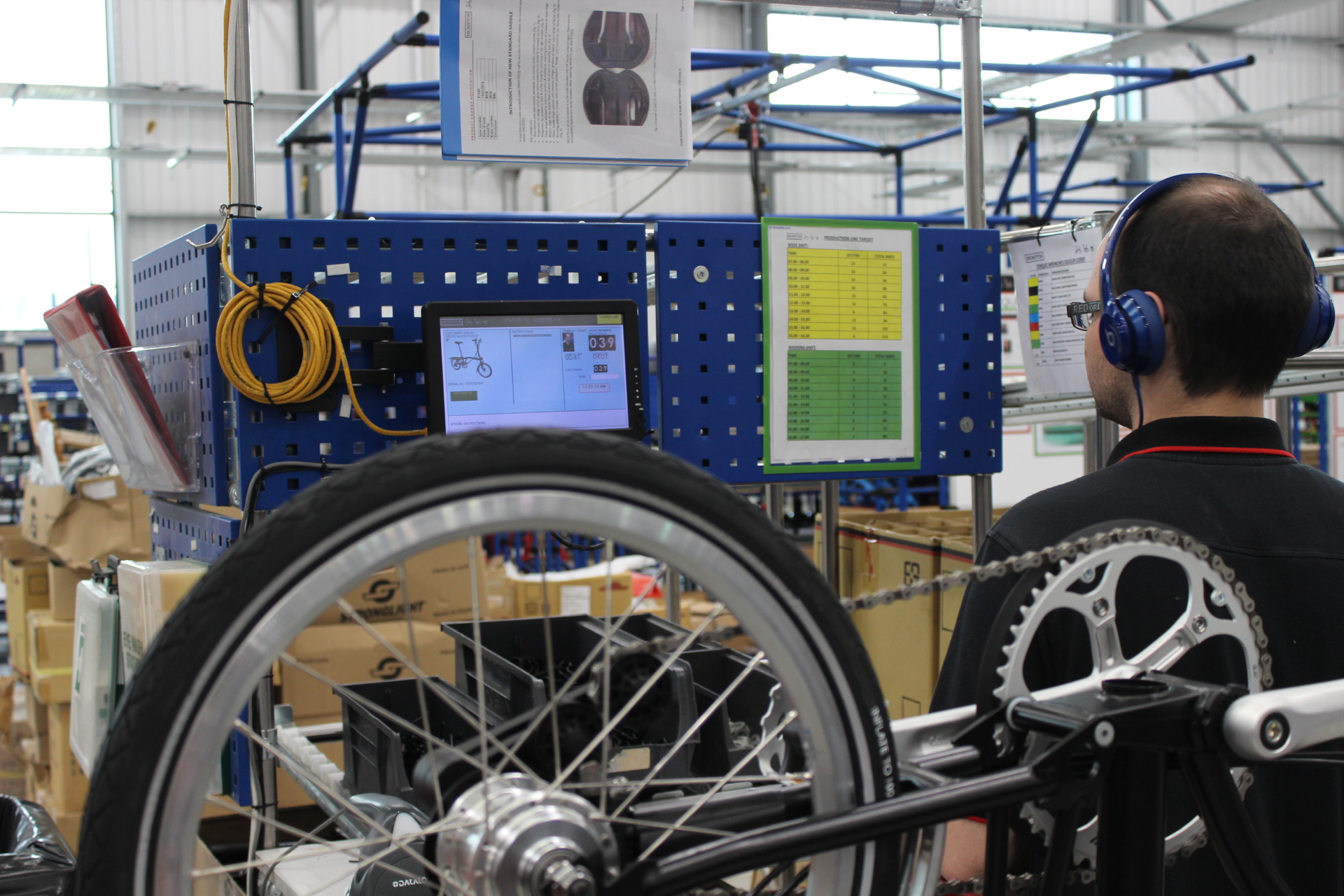

Brompton folding bicycles has a new home. At 84,000 square foot, the new Greenford factory is four times the size of the previous premises at Kew Bridge.

This development for Brompton is a bit like moving out of a maisonette and into a four bedroom home. The company could have gone half way and settled for a two bedroom flat, but this new premises gives them room to triple their production and with Brompton Electric bikes due imminently they intend to do just that.

Brompton Bikes: Buyers Guide Review & Tips

The upheaval set the company back two-million-of-your-English-pounds, and they’re the first to admit that moving away from London may have been cheaper in the short term. However, with roots going back to 1975 when Andrew Ritchie designed the first bikes in his flat opposite the Brompton Oratory and 44 in house brazers who have been through an 18 month training course, a move away from the city could cost them both the heritage and the expertise that sets the company apart.

Looking around the factory is a treat. Taking the tour on a sunny Wednesday morning, my tour guide is Brompton PR executive Nick Charlier and we start at the heart of Brompton: brazing.

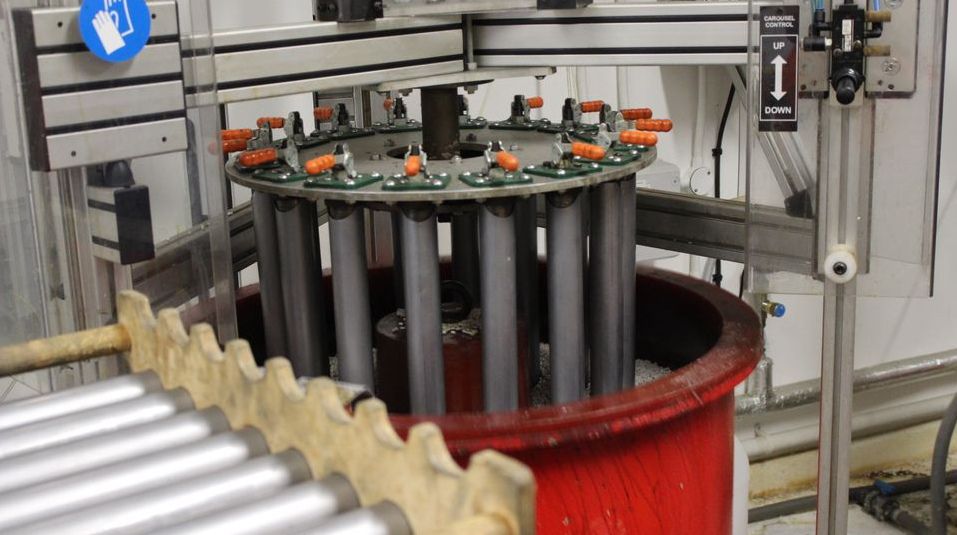

Brazing is another thing that makes Brompton different compared to the majority of other manufacturers these days. It’s the process of joining metal tubes together using a filler metal – in Brompton’s case brass is melted to fuse together steel components. The brass has a lower melting point, which means that the steel is subjected to less stress and distortion than it would be in the case of a more commonly used weld, when the tubes themselves are melted to form a join.

Charlier tells me: “We use brazing because it’s basically the strongest way of building a bike, the process we use is one of the reasons our bikes last so long. We could move to the Midlands or Wales, where it’s much cheaper – but it takes 18 months to train a brazer.”

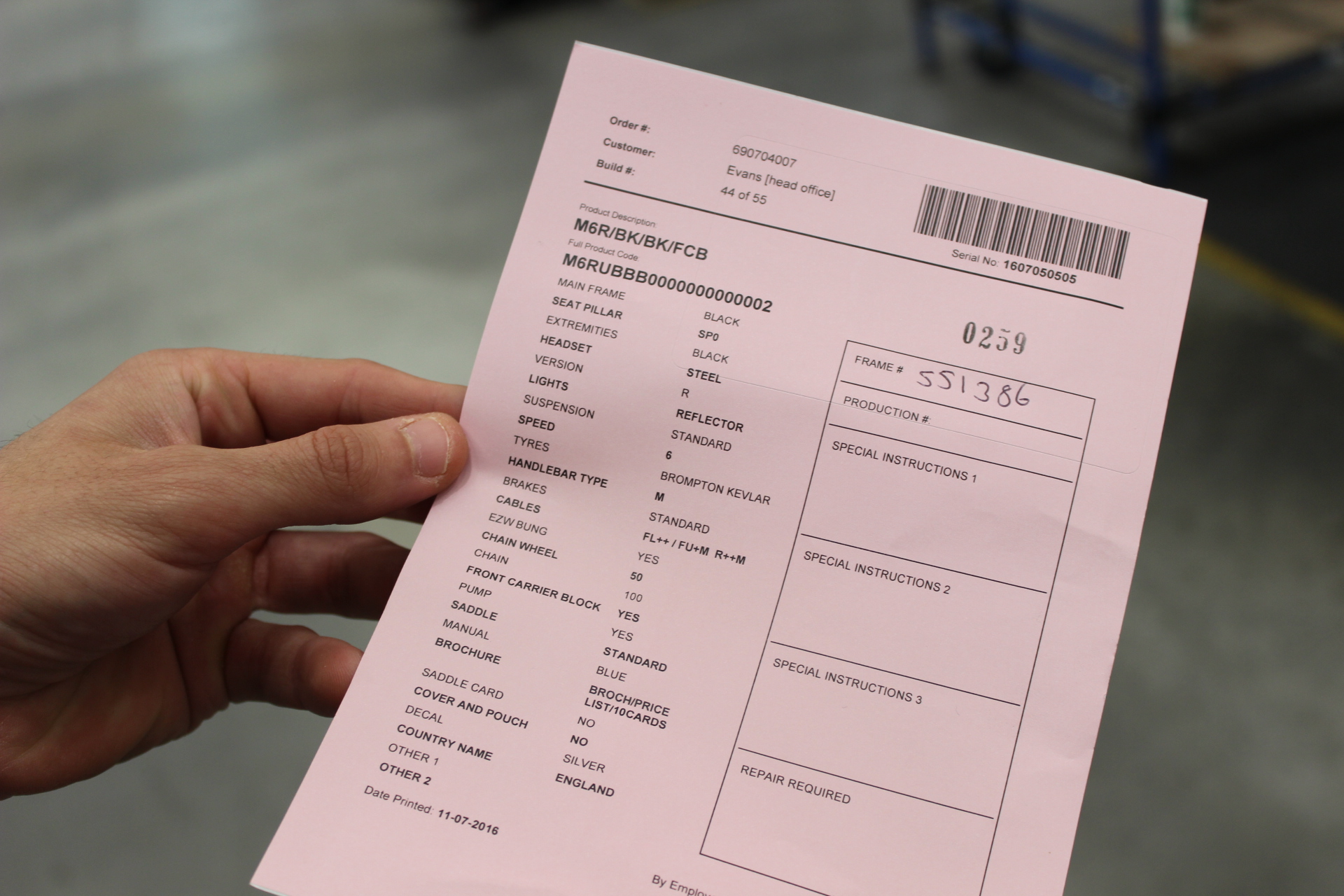

It’s refreshing to see a company place so much value in its employees – from the initials every brazer leaves on each part they work on to the chart which shows each brazer’s style at the end of the bay. Charlier tells me: “When you’re a kid you get taught handwriting, but everyone has their own style. It’s the same with brazing. Everyone has their own technique.”